The Haute Couture Dolls of The French Recognition Train

The freighter Magellan arrives outside New York City on February 2, 1949.

An obscure collection of haute couture dolls handmade as a gift from France to the United States soon after the end of World War II has been kept hidden away for decades in a New York City museum. The fact these dolls exist at all is a well-kept secret known by few, even among those who adore fashion. What’s more, the accuracy of what is known or believed to be known about them has been called into question.

Page from the French Catalog Haute Couture Dolls which was made in either December, 1948 or January, 1949.

Though the story of the train probably begins much earlier, the one related to these extraordinary dolls begins in 1947 when journalist Drew Pearson, who was determined to see his nation exercise compassion for the devastation Europe had suffered during the Second World War, encouraged Americans to donate seven hundred boxcars of supplies as a relief to war-torn France and Italy. Known as the Friendship Train, these boxcars were not sent by federal or state governments but by individual US citizens, and carried $40 million in food, basic staples, and medical supplies to the two countries to help in their efforts to recover from the catastrophic events of the Second World War.

Front page of the Ames Daily Tribune, November 4, 1947.

The boxcar supplies Americans sent to Italy arrived on Christmas day in 1947. An Italian film company documented its arrival and made a film about the distribution of food to “their destitute citizens.” The film was sent to the United States with the request that copies be made so movie theaters across the country could show the documentary to the people who had made such an impact on the devastated country. The request was granted and the film was shown from coast to coast.

The American Friendship Train makes a stop on its route between Paris and Marseille.

Each country showed its gratitude for the boxcar supplies in their own way. Italy showed its thanks in the summer of 1951 by offering to cast and gild four enormous bronze sculptures for the US. The four were finished that autumn, and two were placed on the abutments of the Arlington Memorial Bridge and two upon the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge.

France, meanwhile, chose to respond in kind in 1949 with what has been called the “greatest thank you note of all time” and sent Le Train de la Reconnaissance Française, or the French Recognition Train (which became colloquially known as the Merci Train or the Gratitude Train) to the United States. The merchant ship Magellan was chosen to carry the Train to the United States. She carried forty-nine boxcars packed with gifts of gratitude, for a total of 250 metric tons’ worth of cargo.

French workers sort gifts at a triage station in Paris, undated. From the Library of Congress, Lot 5899.

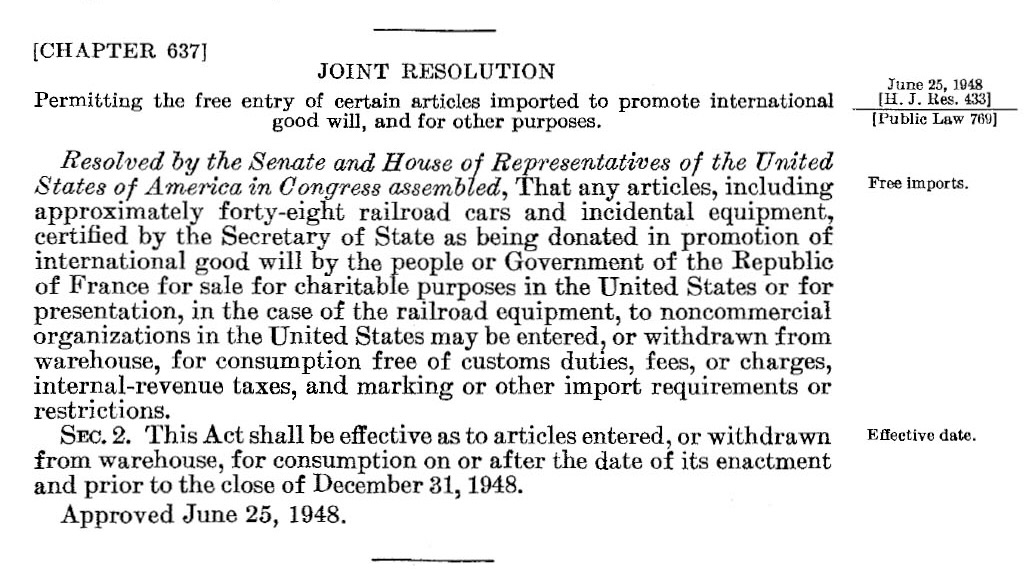

But accepting the train and her cargo was not a simple affair. It took much longer than anticipated to work out all the details. The Marshall Plan - an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe - had gone into effect, and something close to $150 billion (adjusted equivalent) in foreign aid was contributed by the US to the economic recovery of Western Europe. Special permissions had to be obtained for the Train to enter the US, and for the US to be able to accept the goods; with the Cold War on the horizon, even the appearance of financial impropriety (or God forbid, potential Communist sympathy!) threatened the project many times. But finally on June 25, 1948, President Truman signed Chapter 637 of Federal law, a Joint Resolution unifying House Resolution 433 and Public Law 769. This law was a special law allowing the ship and its contents to enter the United States duty-free, and was “certified by the Secretary of State as being donated in promotion of international goodwill.”

Joint Resolution between House and Senate Chambers to admit the Magellan and her contents duty-free. June 25, 1948.

On February 3, 1949, more than 25,000 people went to New York City to see the docking of the merchant ship Magellan. When she announced her imminent arrival, the Magellan was greeted at sea by US Air Force F-80 and F-82 jets which escorted her past Lady Liberty and down the Hudson River to her eventual berth in Weehawken, New Jersey. On each side of the freighter, without permission from the French organizing bodies which had planned this gift in great detail, the crew of the Magellan had painted the words, “MERCI AMERICA” in white painted letters three meters high. To the French this boxcar train may have been Le Train de la Reconnaissance Française, but to the Americans - who have always responded well to clever branding! - the phrase was immediately appropriated and became forever known as the Merci Train.

Regardless of what the train was called, the forty-nine boxcars were each stuffed with gifts to America. One boxcar was intended for each state in existence at the time, with the last to be shared by Washington, D.C. and Hawaii (as Alaska and Hawaii did not become states until 1959). The then-mayor of New York City, William O’Dwyer, and French ambassador Henri Bonnet led the ceremony welcoming the French Recognition Train to America. “The crowd was even bigger than for Lindbergh’s memorable return after his flight across the Atlantic.” Life Magazine covered the arrival with a full-color spread of photographs.

Henri Bonnet, French Ambassador to the United States, speaking at the Merci Train welcome ceremony on February 6, 1949. Harry S. Truman Libray & Museum.

Once the French train arrived and docked in the shipyard in Weehawken there was a bit of a delay. The boxcars were configured for French railroads, not American ones (for simplicity’s sake - think of it as similar to the difference between the metric and imperial systems) and had to be loaded onto American flat-bed railway cars for transport. They were then sent on carefully planned routes that would disperse each to its intended state. The first priority (and first boxcar after the one intended for New York, which arrived at its destination before any other) was sent down to Washington, DC. Other convoys of cars went North and West. As the three fingers of trains worked their ways across the United States, they stopped to drop off cars in the various states they crossed through. Every state held a parade or ceremony to celebrate the arrival of its individual car. After the docking of the Magellan, the citizens of New York City participated in its welcome festivities; “an unforgettable moment for the inhabitants of New York.” More than 200,000 people across the country came to “welcome the whole train, but above all the New York wagon that was transported from Broadway to Manhattan.

A crowd gathered around the New York boxcar at the Merci Train welcome ceremony on February 6, 1949. Harry S. Truman Libray & Museum.

The boxcars held as much significance as their cargo. Colloquially, these boxcars were called “forty-and-eights.” The cars had originated as covered wagons intended for hauling commercial goods in the 1870’s. Later, necessity dictated they be converted for use as military transport. The name forty-and-eights refers to the carrying capacity of the cars, which was originally said to be forty men or eight horses. The boxcars had been used multiple times; by France during both World Wars, by the Germans during the French occupation, and finally by the Allied liberators. These were the train cars on which U.S. soldiers had been transported to and from battle during the Second World War. They had not been designed for human travel and had no seating, windows, or bathrooms. About forty soldiers were packed into each car, many of whom never returned home. “Thus, the cars that once carried weary men of war now carried gifts of peace, the “greatest thank you note of all time.”

A crowd celebrates the arrival of the Rhode Island boxcar in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, February 8, 1949.

The dolls themselves, and the concept of miniature historic models of apparel, were the brainchild of Eileen Bonabel. It was the second time such a collection had been produced; the first had been the Théâtre de la Mode, a series of dolls dressed in apparel from the 1947 haute couture collections. Between 1945 and 1946 this first collection of fashion mannequins had been created and had traveled as an exhibit to raise funds for survivors of the war and to help revive the severely crippled French fashion industry. This idea was revived for the dolls on the Gratitude Train, and this next incarnation was intended to be a priceless gift as well as the creation of a collective historic artifact. The dolls were to represent the history of couture, and the Chambre Syndicale (who organized the project) brought together the best haute couture “fashion designers, hair stylists, and accessory designers of the time to create these miniature masterpieces.”

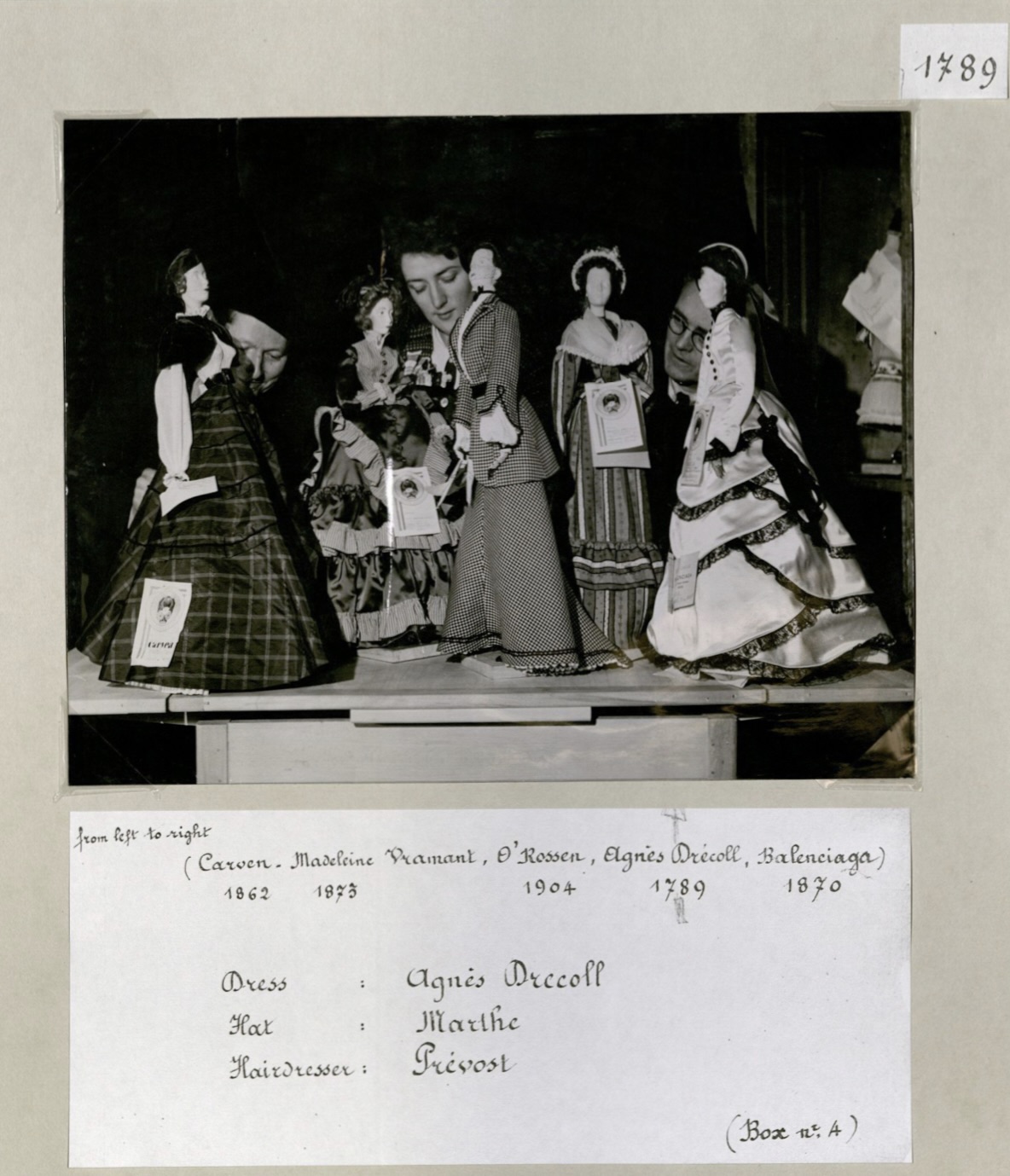

1787 Doll by Mendel, Rose Valois, Rene Rembaud, the 1788 Doll by Jacques Griffe, Legroux, Georgel, and the 1789 Doll by Agnes Drecoll.

Each doll was about 24 inches tall with “exoskeleton-like” open wire armature bodies masterfully shaped from iron. The decision to shape them from iron was both economical and a practical choice. Iron was easily available and lended itself to shaping, which meant the dolls were poseable. Their wire bodies were left purposely exposed, their heads were made of plaster and designed by Catalan sculptor Joan Rebull, and their hairstyles were all made of real human hair. These perfect miniature dolls were dressed in incredibly detailed and historically accurate recreations of clothing worn between 1715 and 1906 by couture and haute couture designers who were “at that time most famous for their achievements.” The fabrics and furs used were donated by well-regarded French and Italian textile firms that had, in some cases, been around for generations.

The 1832 Doll by Marcelle Dormoy, Rose Descat, and Antoine, the 1840 Doll by Pierre Benoit, and the 1845 Doll by Callot Soeurs.

By whatever mysterious means, forty-nine of the best fashion ateliers were selected and each one made a costume for a doll. The dolls were the same as the ones used a few years earlier in the Theatre de la Mode, so everyone who worked on the Merci Train dolls was ostensibly familiar with their format. The choice of dates (1715-1906) was not an accident, either. Every detail of this project was packed with symbolism and historic reverence. The year 1715 was the year French King Louis XIV died; the Sun King had been a great patron of the textile industries in France and “was able to elevate his nation to a position of cultural domination that continued throughout his seventy-two years of reign.” The designer or team of designers working on each doll selected a year they found to be inspirational. The source material the designers referenced for their dolls ranged from fine art and literature to historic fashion plates and records.

The 1791 Doll by Martial & Armand, Evelyne Arzan and Henri Durand.

The dolls were too fragile to ship in the actual boxcars so they were packed separately and numbered. It is unclear if they were cargo aboard the Magellan, though it seems likely that they were, as they were put on display in the windows of a department store located at 590 Madison Avenue on February 8th or 9th, 1949. Virginia Pope, one of the first famous fashion writers for the New York Times, wrote an extensive piece about the dolls and that first exhibition.

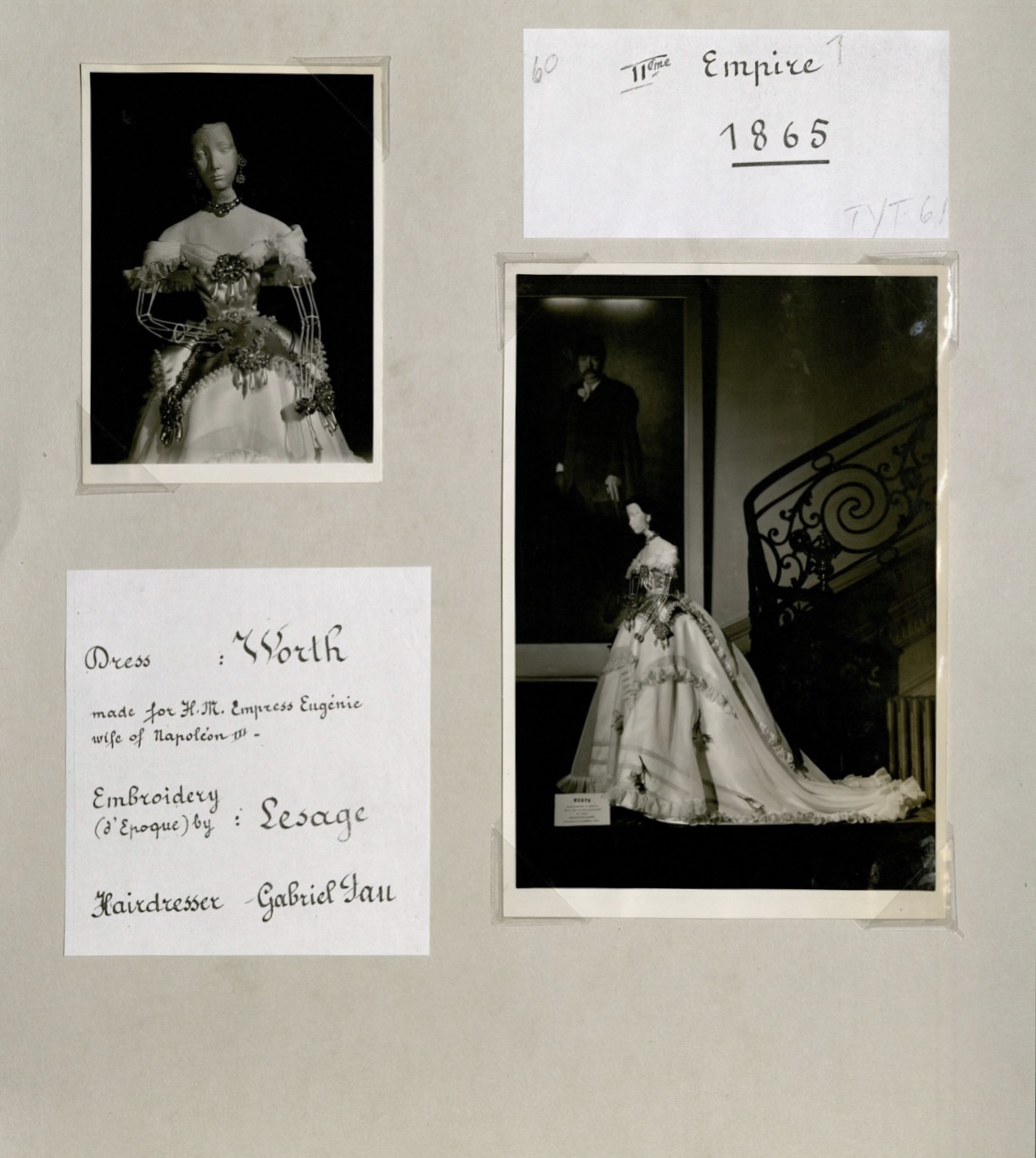

The 1865 Doll by Worth, Lesage, and Gabriel Fau and the 1866 Doll by Marcelle Chaumont and Georgel for Caroline Reboux.

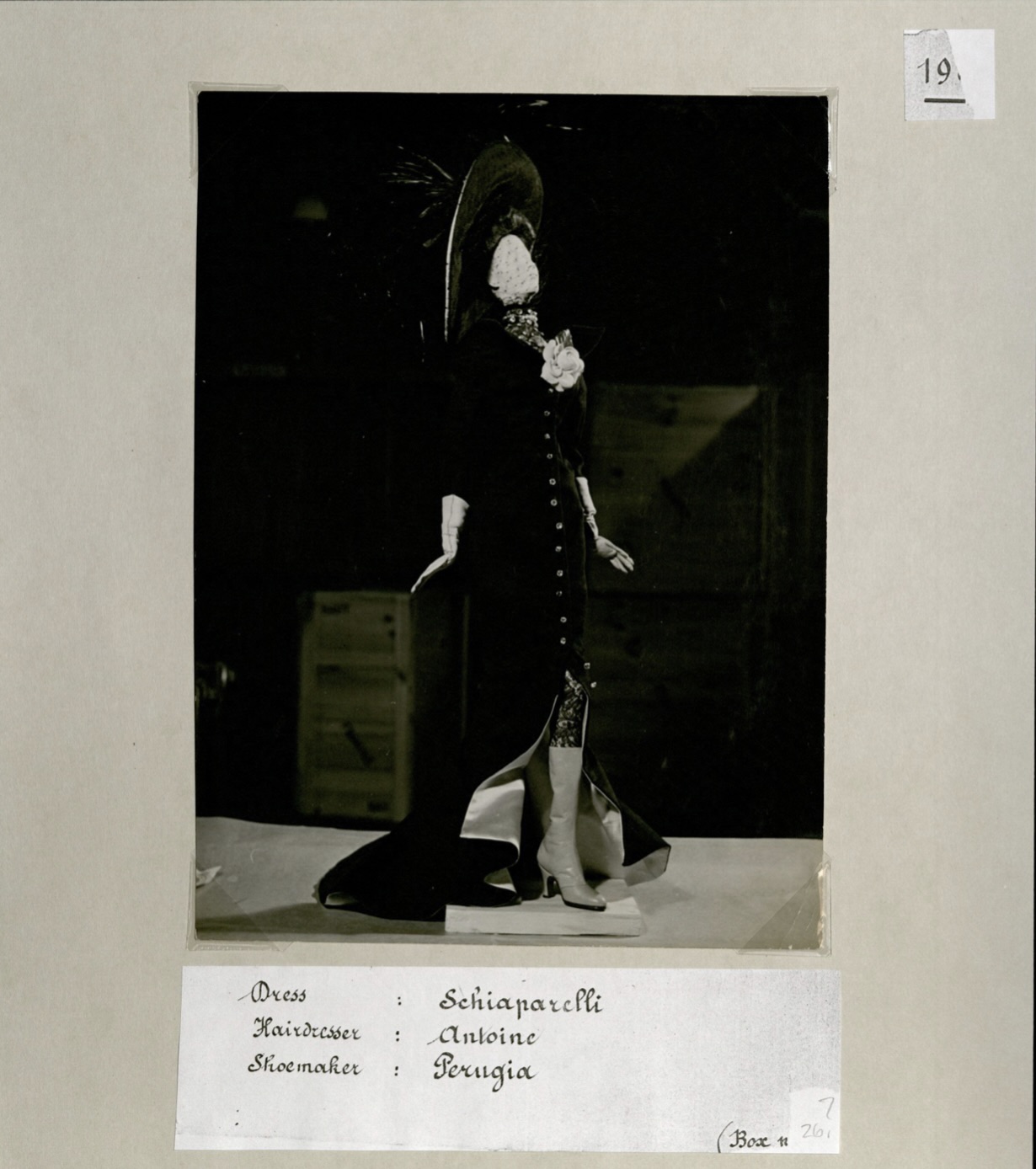

It is not clear if the French supported this, but the original intention of the Americans was to disperse the dolls with the boxcars. One would go to each state, and one would go to DC. But there is correspondence from January 1949 questioning this decision, and it seems the right person (whoever that was) understood the dangers of splitting up the dolls. When the collection first arrived in New York, it appeared The American Federation of Arts would take possession of the dolls with the intention to organize a touring exhibition of the collection that would travel across the United States. That never happened. Instead, the Brooklyn Museum became their home under the auspices of Michelle Murphy, who was at the time running the fascinating Blum Design Laboratory. Murphy’s show went up in September of 1949 and ran through much of 1950. Murphy organized the exhibition, wrote the 1949 exhibition guide, and published a second hardcover copy of her guide the following year. Elsa Schiaparelli and Jacques Fath both attended the opening of the exhibition though they did not travel together, and separate press releases regarding their attendance were released by the Brooklyn Museum. Then the dolls sat in the Blum Design Lab, used for design research.

Page from the French Catalog Haute Couture Dolls; the 1906 Doll by Schiaparelli, Antoine, and Andre Perugia.

Very little happened to the dolls over the next sixty years. Then in December of 2008, due to financial considerations, the entirety of the Brooklyn Museum’s costume collection (including the Merci Train dolls) was absorbed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. The New York Times reported this as an agreement reached by both institutions so that the Brooklyn collection, which had not been holding exhibitions for more than a decade, could be “properly cared for and exhibited.” Yet the dolls remained out of sight until 2021, when the Christian Dior Merci Train doll was featured as part of the Met’s Costume Institute’s Dior Retrospective. Then the collection of French dolls was quietly deaccessioned back to Brooklyn.

Page from the French Catalog Haute Couture Dolls; the 1865 Doll by Worth, Lesage, and Gabriel Fau.

While the majority of the boxcars still exist today and in most states there are museums dedicated to the preservation of their memory, the dolls have suffered a different fate. They have never been shown as a collection since their initial exhibition in 1949-1950 and have only been pulled individually for shows in the years in between. Otherwise, they have remained in storage under the careful care of conservators. What’s more, the records concerning them which have survived (and which have been carefully documented by a community of individuals around the world who are dedicated to preserving the memory of the French Recognition Train) are incomplete and often pose more questions than they answer. The collection is not a complete set today; reports vary, but as many as five to seven dolls might be missing or damaged. The Worth doll disappeared at some point during its storage at Blum Design Lab, possibly because it had been pulled to decorate the office of a museum executive. The Library of Congress has a photograph of a 50th doll with an inscription on the back which explains that she was a spontaneous gift by the workers in Germaine Lecomte’s atelier and was intended as their contribution to the French Recognition Train. Almost no one on earth even knows that she exists, and no one can tell you where she is today. And there is no information to be found about the current state of the collection

Photo of the missing Germaine Lecomte Doll, Library of Congress, Lot 5899. The inscription on the back reads: Mannequin offeir par Pes ouvries de Pa Maison Germaine Lecomte. Sponiamientant.

Since 2018 fashion historian Rachel Elspeth Gross has run her popular blog, Today’s Inspiration, about the history of high-end fashion design. Drawing more than 40,000 individual readers every day; Rachel’s ever-growing audience includes some of the biggest names in Fashion, Haute Couture, Fashion Journalism, and Fashion History academics. Her work has been featured in Women’s Wear Daily, the New York Times, Italian Harper’s Bazaar, and The National News; writes for The Vintage Woman magazine. A formally trained designer in her own right, in her spare time Rachel recreates 19th century ball gowns from scratch.

SOURCES

FRANCE TO GREET U.S. FOOD-GIFT SHIP; Cargo of Friendship Train to Reach Le Havre Tuesday -- Nation Is Grateful. December 14, 1947. The New York Times, New York.

Children of Paris Wildly Acclaim Arrival of Food Gifts From U.S.; CHILDREN IN PARIS CHEER FOOD TRAIN by Mallory Browne. December 21, 1947. The New York Times, New York.

FRENCH COLLECT GIFTS; 'Train of Gratitude' for U.S. Aid Gathers Momentum. October 27, 1948. The New York Times, New York.

FRENCH ACCLAIM U.S. AID; 22 Members of Academy Voice Gratitude for Help. November 26, 1948. The New York Times, New York.

Press Release: DEUX SIÈCLES D’ÉLÉGANCE FRANÇAIS RECONSTITUÉS POUR LE

French Catalog Haute Couture Dolls, The either December, 1948 or January, 1949. La Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne.

La Couture à Paris ou Le goût de l'idéal by Louise de Vilmorin et Colette. 1949. The Paris Almanac.

Press Release: Robe commandée à Worth par S.M. l’Impératrice Eugénie en 1865. January 11, 1949. Maison Worth. Paris.

FRENCH GIFT TRAIN SAILS; 49 'Thank You' Cars Are Due to Reach Here Jan. 30. January 15, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

'MERCI' TRAIN HERE FEB. 2; Gifts From France in 49 Cars Will Go to State Capitals. January 22, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

PLANS TRAIN WELCOME; Committee to Greet French Gift Collection on Ship. January 27, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

CITY SET TO GREET FRIENDSHIP TRAIN; Thousands of Students Here Will Go 'All Out' at Formal Reception Thursday. January 30, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

GRATITUDE TRAIN DOCKS WEDNESDAY; 49 Freight Cars Bearing Gifts of French People for U. S. Due Here Aboard Ship. January 31, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

French Gift Train Receives Warm Welcome on Arrival; GRATITUDE TRAIN GREETED WARMLY by Joseph J. Ryan. February 3, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

WASHINGTON HAILS GRATITUDE TRAIN; France's 'Merci' Cars Finish Run From Jersey City -- Civic Greeting Today by William R. Conklin. February 6, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

Capital Hails Train As 'Heart of France'by William R. Conklin. February 7, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

GIFTS FROM FRANCE PUT ON VIEW HERE; State's Share of Treasures Seen at Evening Ceremony -- Public Invited Today. February 8, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

Le Train de la Reconnaissance Française by M. Gaveau. Undated, presumably 1949. Le Rail, France.

PARIS COUTURE GIFT OF DOLLS EXHIBITED; Costumed by Noted Designers, They Show Two Centuries of Women's Styles by Virginia Pope. February 9, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

FRENCH DOLLS ON DISPLAY; Two Centuries of Costumes Are Added to Exhibit Here. February 16, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

MUSEUM TO GET DOLLS; French 'Merci' Train Costume Gifts Go to Brooklyn. April 5, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

Brooklyn Museum Press Release: “MERCI TRAIN” DOLLS GIVEN TO BROOKLYN MUSEUM. April 6, 1949 and September 1, 1949.

Museum Gets French Dolls. April 6, 1949. The Daily News, New York.

CHATTER! September 22, 1949. The Daily News, New York.

Contemporary Comment: Schiaparelli Greets Press; Talks Fashions by Ruth G. Davis. September 23, 1949. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, New York.

Brooklyn Museum Press Release: SCHIAPARELLI VISITS FIRST MUSEUM SHOWING OF FRENCH FASHION DOLLS AT BROOKLYN MUSEUM. September 25, 1949.

Doll Exhibit Preview To Be Held Tomorrow at Brooklyn Museum. September 25, 1949. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, New York.

Brooklyn Museum Press Release: FATH TO ASSIST AT OPENING OF BROOKLYN MUSEUM EXHIBITION OF FRENCH COSTUME DOLLS. September 26, 1949.

FRENCH DOLLS IN EXHIBIT; Brooklyn Museum to Show Styles From 1715 to 1906. September 26, 1949. The New York Times, New York.

Two Centuries of French Fashion Elegance, September 26, 1949 through January 08, 1950; Exhibition Book by Michelle Murphy. The Brooklyn Museum.

Two Centuries of French Fashion Elegance; An Album of Mannequin Dolls, by Michelle Murphy. 1950. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York.

Théâtre de la Mode: Fashion Dolls : the Survival of Haute Couture by Edmonde Charles-Roux, Herbert R. Lottman, and Stanley Garfinkel. Palmer/Pletsch Publishing; Revised second edition (September 1, 2002)

Dior to Bring Retrospective to Brooklyn Museum in September, by Joelle Diderich. June 4, 2021. Women’s Wear Daily.